Subscribe

Data delivered to your inbox. Keep up with the latest developments.More than 1,700 assets targeting people in Middle East and North Africa removed.

On February 29, 2020, Facebook removed a network of assets engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior targeting audiences in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). These assets were linked to two marketing firms, NewWaves and Flexell, that were at the center of two separate purges in August and October 2019, respectively.

In its announcement, Facebook said:

We also removed 333 Facebook accounts, 195 Pages, 9 Groups and 1194 Instagram accounts that were involved in foreign interference emanating from Egypt that focused on countries across the Middle East and North Africa. […] Although the people behind this activity attempted to conceal their identities and coordination, our investigation found links to two marketing firms in Egypt — NewWaves and Flexell. Both these companies and individuals associated with them have repeatedly violated our Inauthentic Behavior policy and are now banned from Facebook.

The DFRLab corroborated the link to NewWaves but was unable to corroborate any direct connection to Flexell.

Facebook provided the DFRLab a subset of these assets consisting of seven Facebook groups, 73 Facebook pages, and 1,191 Instagram accounts ahead of the takedown and was able to corroborate the company’s assessment of inauthentic and coordinated activities between these assets before they were removed by Facebook.

The assets bear familiar hallmarks reminiscent of previous campaigns orchestrated by marketing companies NewWaves and the similarly named Newave, registered in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, respectively. In August 2019, the DFRLab published an investigation into the network shortly after Facebook removed those assets.

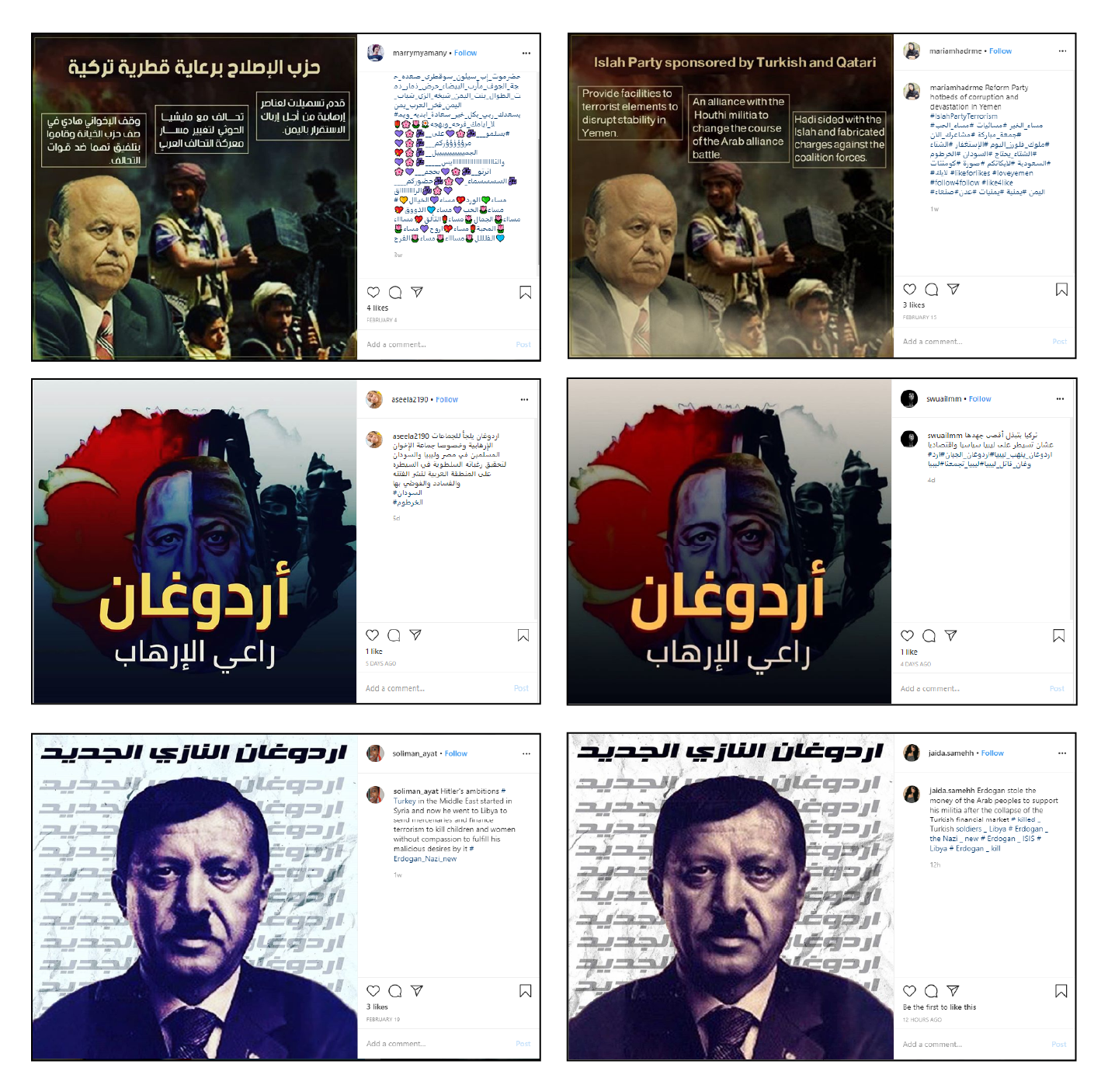

The investigation found evidence that the network’s Facebook and Instagram assets coordinated their activity and that a related set of Twitter accounts appeared to be a part of the same campaign. The existence of a Twitter network operating in unison with assets on Facebook is also reminiscent of a BuzzFeed investigation into Flexell’s operations published in October 2019. The network repurposed the same memes and images, even across platforms, sometimes performing minor alterations or translations to suit a different audience.

The Instagram and Facebook assets interspersed uplifting and humorous content with politically charged narratives, presumably to garner a wide following before pivoting into regional politics. These assets targeted countries in the MENA region, including Turkey, Iran, Qatar, Bahrain, Sudan, Somalia, and Libya among others, with Facebook adverts meant to promote the network. Despite being targeted at these countries, the administrators for these pages were mostly based in Egypt.

The DFRLab found that the network created fake Facebook accounts, using publicly available images, to act as administrators for these groups. Most of the Facebook and Instagram assets were postured as females, likely as a means of targeting a male demographic.

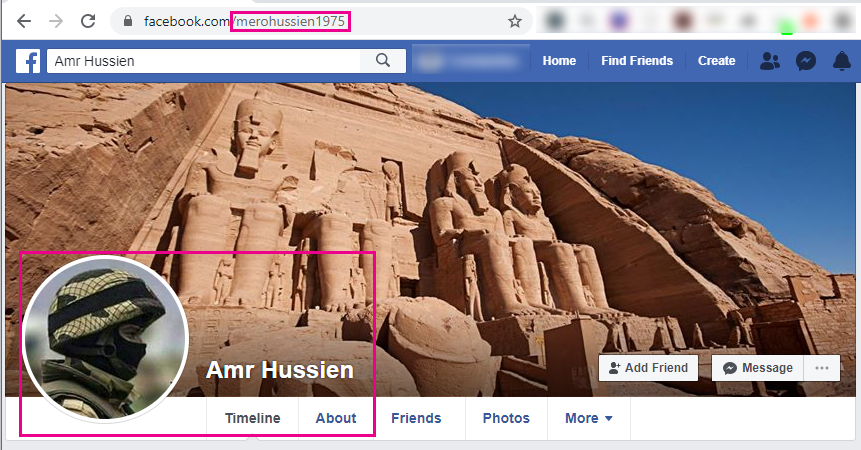

Finally, the DFRLab linked the off-platform websites featured in this subset of Facebook assets to similar websites seen in the earlier takedown of NewWaves assets August 2019, through analyzing the WordPress files the sites used. The main suspect behind this network was NewWaves’s owner, Amr Hussein, who was identified as a former military officer and self-described expert in “internet warfare” in a New York Times piece following the removal of the assets by Facebook. Hussein used the pseudonym “Amr Hussien” for the Facebook profile and website registration records linked to him in this investigation.

Birds of feather

Each assets’ role within the network goal was varied; while some of the Instagram accounts, Facebook pages, and Facebook groups were overt in their political messaging, others postured as benign platforms sharing humorous or uplifting content, promoting fashion, or presenting as regional civilian news outlets. Still others leveraged large followings to provide engagement to other assets and off-platform websites linked to the network.

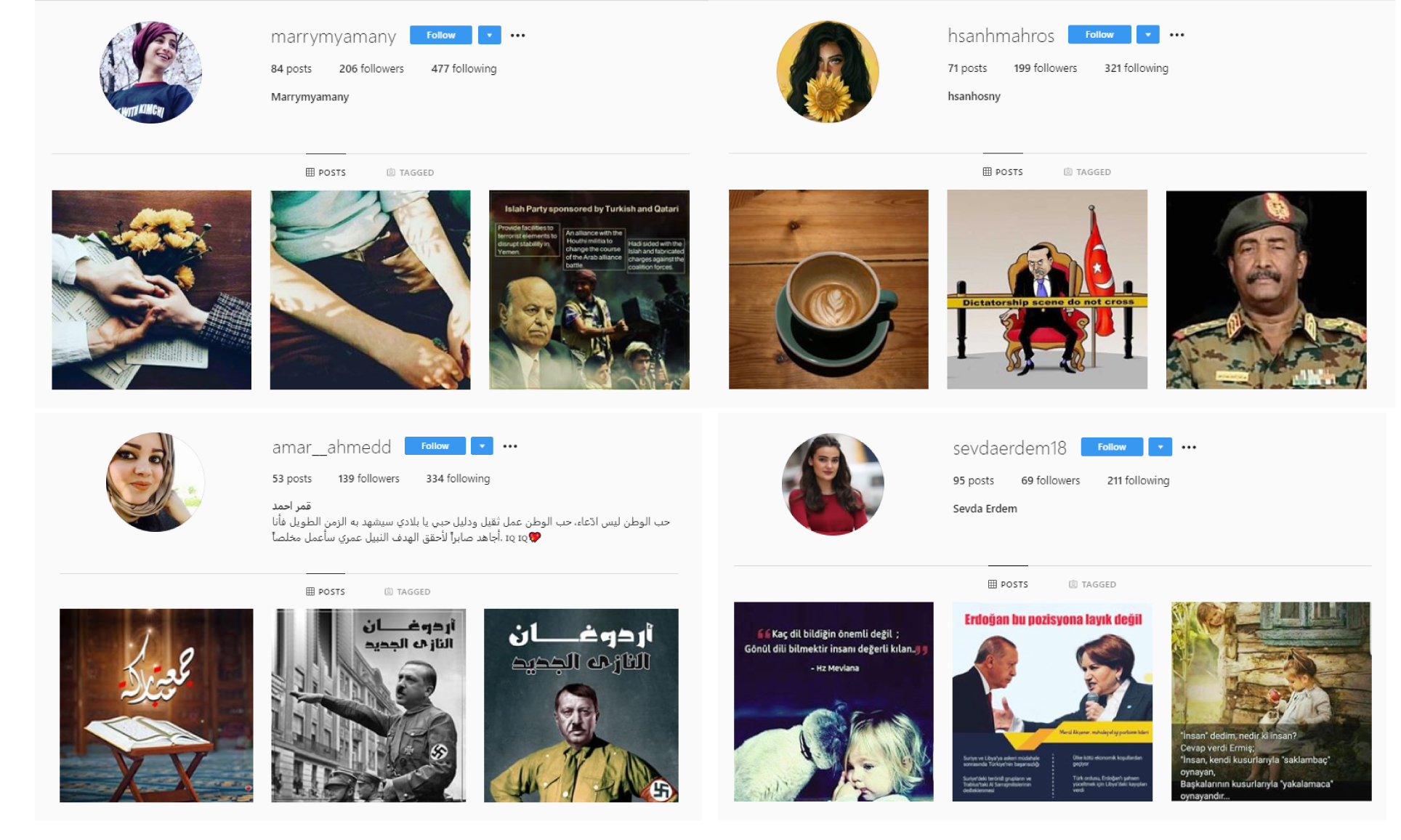

The overtly political assets were particularly critical of Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Some of the images the assets posted likened Erdoğan to Adolf Hitler by photoshopping the Turkish head of state into a Nazi uniform or adding Hitler’s toothbrush mustache to his appearance.

A subsection of the accounts dedicated to regional interest focused on Yemen, Somalia, the United Arab Emirates, and Lebanon. Yemeni accounts spoke out against infighting and attempted to empower the Yemeni people around a shared discontent for the country’s Al-Islah reform party, which is associated with the Muslim Brotherhood.

The content on these pages spanned the MENA region, and most of the Facebook pages were administered by accounts based in Egypt.

Deja view

The DFRLab’s investigation revealed evidence of coordination between the assets on each platform (e.g., Instagram to Instagram, Facebook to Facebook) as well as across platforms (e.g., Instagram to Facebook).

Images used on Facebook assets were repurposed for use on Instagram assets, and vice versa. The images were altered slightly, presumably using one or more of the application’s built-in filters, in what was likely an attempt to circumvent the platform’s automated detection systems.

Between the Instagram assets, images were propagated with minor changes to the content. For example, an image President Erdoğan (found nestled between posts about women’s fashion) was used by different accounts but translated into different languages each time.

This variation in the content suggests intentionality, either responding to the need for original content to build a following or to evade Facebook’s content moderating techniques.

A majority of the observed Instagram assets appropriated female profile pictures and on occasion captioned posts in the first person, purporting their female identities. By gendering the accounts as female, the administrators of these assets presumably hoped to maximize its impact on a likely male target audience.

Denial Delta

In examining the Facebook pages and groups provided by the company, the DFRLab identified several related and seemingly inauthentic accounts that were responsible for administering and moderating the groups in the subset provided. Facebook confirmed they were connected to the set and subsequently removed these accounts as part of its ongoing continuous enforcement.

The administrator accounts made use of inauthentic profile pictures sourced from elsewhere on the internet. For example, the administrators for the Facebook group صفقه القرن (“Deal of the Century”) used images of Lebanese author and human rights activist Joumana Haddad, Egyptian actress Yasmine Sabry, and an Iranian model for their profile pictures.

In some of these cases, the accounts reused images used by other administrator accounts. “Hala Mansour,” one of the accounts discovered during the investigation, used the same image as its cover photo that another administrator account, “Farida Hassan” used as its profile photo.

Using pictures of favorite celebrities or inspirational public figures is not an indicator of inauthentic behavior in of itself, but when considered that the same behavior presented across multiple, apparently unconnected groups in the network of Facebook assets, this behavior appears less benign.

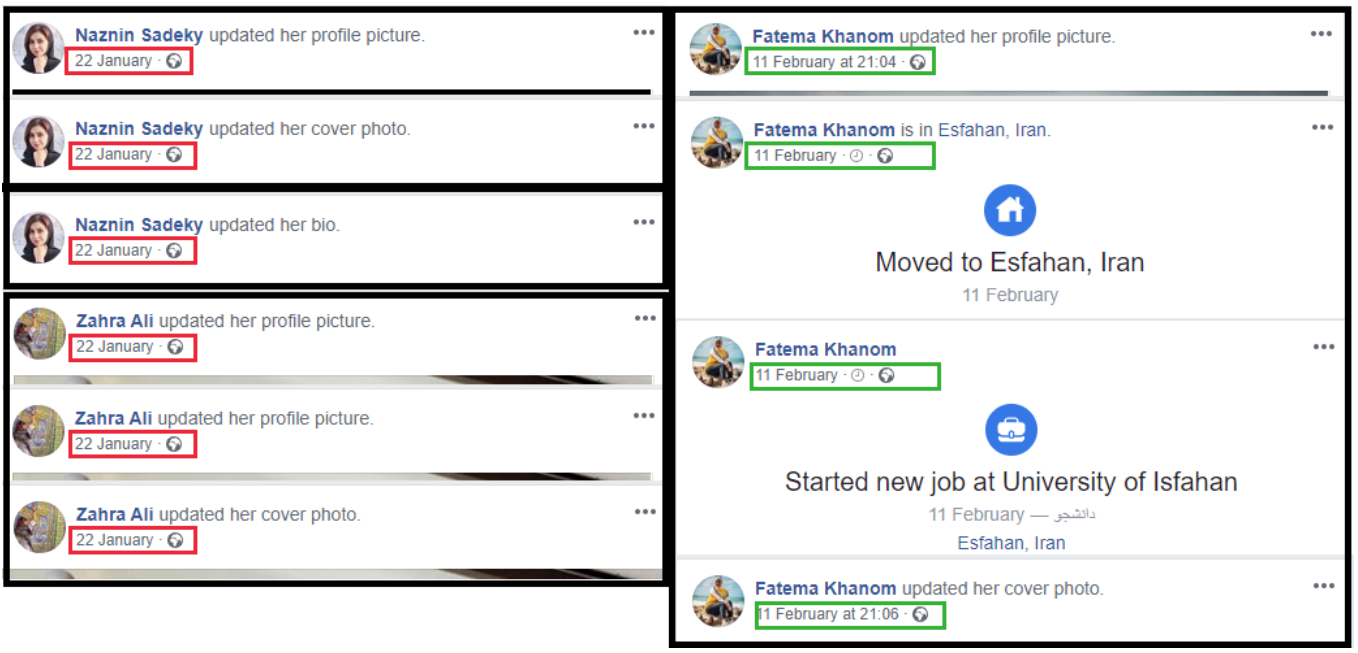

Secondly, it appeared that most of the administrator profiles may have been created as recently as early 2020. While new Facebook accounts are constantly created, it is unusual that all the administrators for these groups only recently created their accounts.

Facebook does not provide publicly the creation dates for accounts created on the platform. Determining when an account was created, or at least when it became active, can be approximated based on changes made to the accounts’ profile, particularly their profile and cover photos.

These administrator accounts consistently made changes to their accounts during short windows, usually updating their profile pictures, cover photos, and biographic information in the process.

Badvertizing

The assets in the network were promoted and amplified using Facebook’s advertising platform to target ads for audiences across the entire MENA region. This was despite the fact that the page administrators, when visible, were all based in Egypt at the time.

The prevalence of these adverts, driving paid-for traffic to assets that bear little indication of any commercial interests, are indicative of an influence campaign aimed at these same audiences.

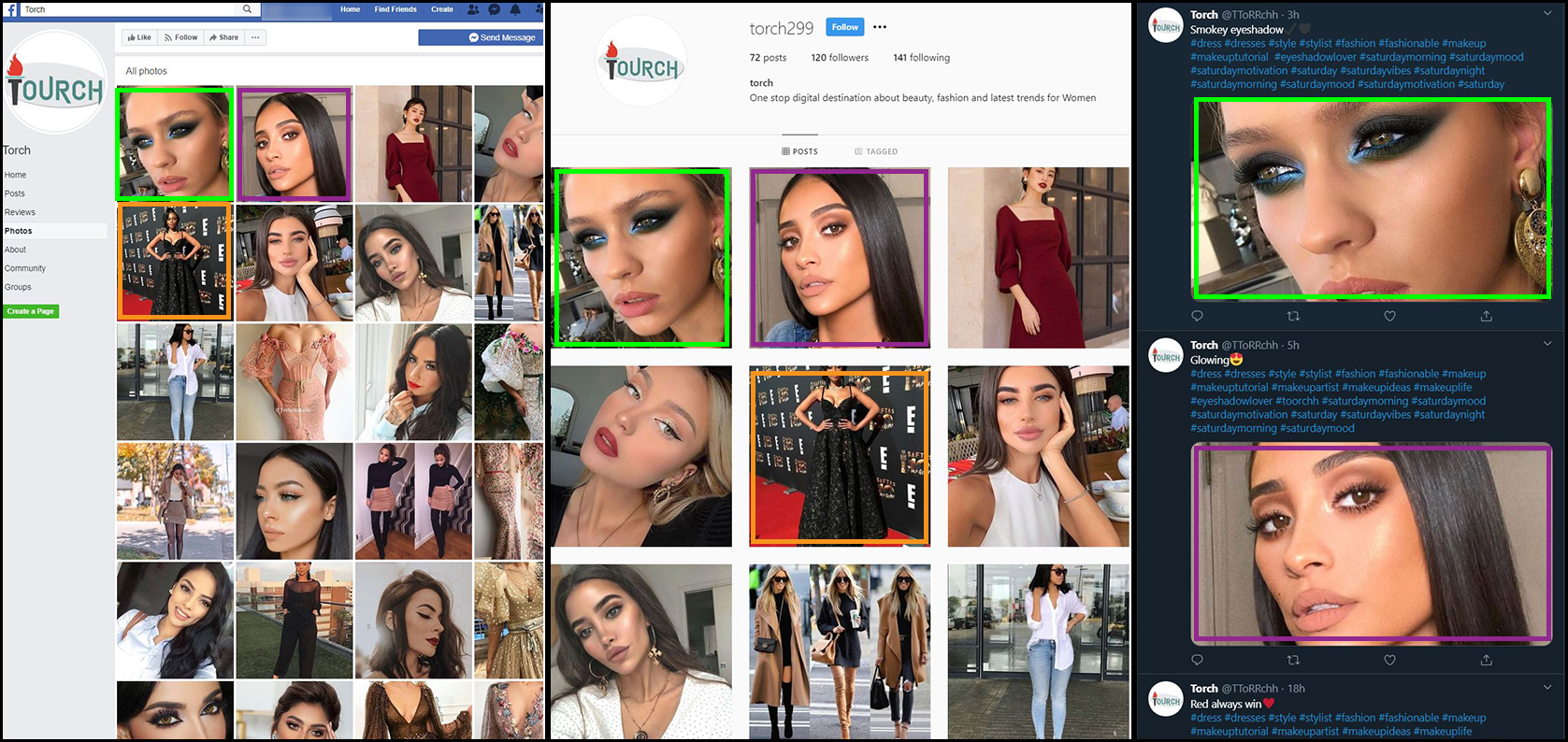

Another feature of these assets was their proliferation across all three social media platforms, using similar and sometimes identical accounts and content across Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

An example of this was Tourch, a business persona that was active on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram at the time of the purge. The Tourch assets published the same pictures of makeup and dresses, usually within seconds of one another.

Sine (wave) qua non

In the dataset Facebook provided for the assets it removed in August 2019, many of the Facebook groups and pages contained links to off-platform websites, which assisted in identifying the person responsible for registering those websites, Amr Hussien — an alternate spelling of the name Hussein.

This time, only two links to off-platform sites were included in the dataset: LebanonTrends.com and Balakona.com. A third, apparently unrelated website and its Facebook page — 7ady3raf.com — was identified during the course of the investigation after links to its page were found on three of five largest pages among the assets: أهتمام — Ahtmam (Interest19), عيون القلب (3yoonalb), and روائع عامة (Rawaeama).

A CrowdTangle analysis confirmed that links to the 7ady3raf.com website was shared to four Facebook pages; the three pages mentioned above, and a fourth link was shared to a second-hand goods page by a user called “Amr Hussien.” The same Amr Hussien account was also an administrator of Deal of the Century, the Facebook group discussed earlier in this piece, and served as an administrator alongside the accounts using actresses as their profile pictures.

Facebook confirmed to the DFRLab that the “Amr Hussien” account, seemingly that of the owner of NewWaves, was removed as a part of the takedown set.

None of these websites were registered in the name of either NewWaves or Hussien/Hussein, but the DFRLab investigation linked all three websites to the network of websites contained in the August 2019 purge. These, in turn, were linked with NewWaves.

While the 7ady3rad.com Facebook page has been removed, Facebook confirmed that it was removed not as a part of the NewWaves takedown but as a part of continuing enforcement stemming out of the DFRLab’s research around the takedown set.

Pressed for words

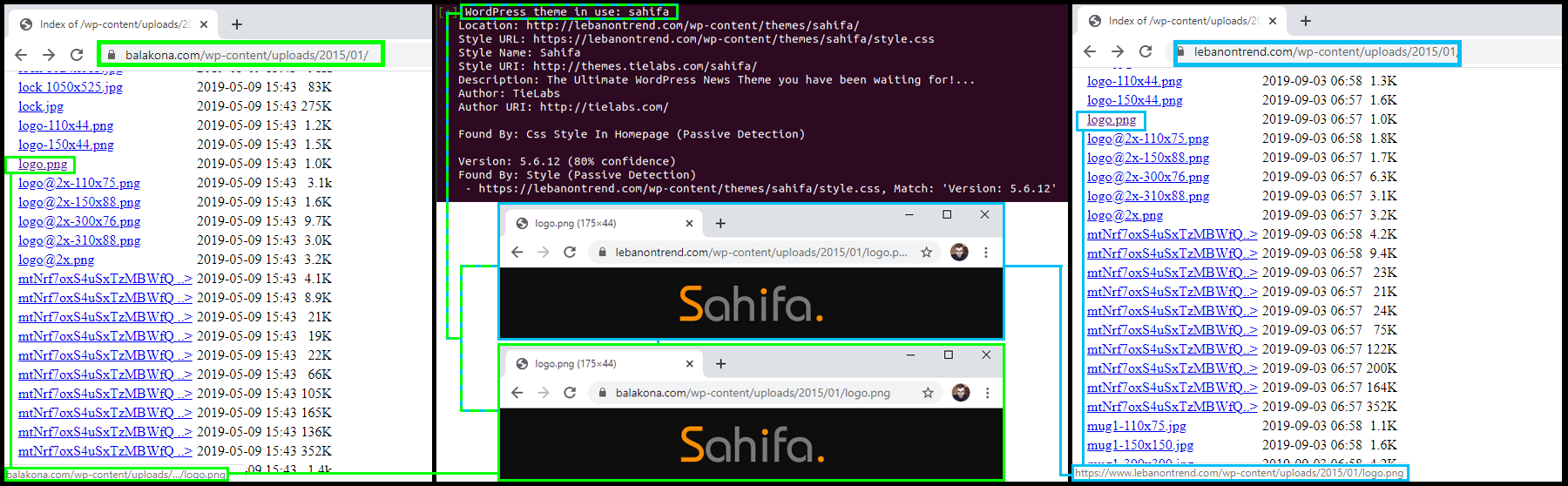

All three of the off-platform websites were developed using WordPress, a platform that allows users to set up and create their own websites without any coding experience. This allowed the sites to be analyzed using WPScan, an open-source WordPress vulnerability scanner, and some similarities between the three websites were immediately apparent.

First, both balakona.com and lebanontrend.com had their WordPress uploads folders exposed. Most website developers disable access to these folders, which contain backups of image and video files uploaded to the site.

With these folders exposed, simply pointing a website browser to each website’s /wp-content/uploads/sites/3 folders allowed manual access to their contents.

The analysis of the folders revealed that “Sahifa,” a news-oriented website theme, was deployed across all both Lebanontrend.com and Balakona.com websites at some stage of their lifecycle. WordPress allows users to install themes to change the look and feel of a website without the owner needing too much technical or creative expertise.

While different websites using the same WordPress theme is not peculiar by default, it becomes suspicious when taken in conjunction with the fact that at least three other websites — freeiranrevolution.com, Syriatrends.com, and alyamanianews.com — linked to the previous NewWaves takedown from August 2019, also used the same theme for their websites.

In addition, access to the image backups established further links between the assets in the network. The image file used as the logo for the Lebanontrend.com website bore the name of one of the Facebook pages in the network, “Moroccos news.”

The WPScan analysis also revealed that balakona.com, lebanontrend.com, and 7ady3raf.com share a number of common usernames used to access the backend of the WordPress site with websites in the August 2019 takedown. Variations of the name Michael, Khafaga, and Mohammed were present, as well as “mero75.”

Of particular interest was the “mero75” username, used to access 7ady3raf.com (from the current network) and freeiranrevolution.com (from the August 2019 network). This username bears a striking resemblance to the Facebook username assigned to the Amr Hussien account seen throughout this investigation.

These findings were corroborated with the results from a WHOIS registration information search for the 7ady3raf.com website performed on the GoDaddy website. These records, as provided by the company hosting Hussein’s website, confirmed a registration date of August 13, 2018, using the same Gmail address used to register some of the websites in the August 2019 takedown.

Conclusion

The resurgence of assets linked to NewWaves and Flexell, both subjects of an identical purges performed less than a year ago, is a worrying development. Flexell and NewWaves persisted with conduct that violated Facebook’s terms of service despite both companies losing assets in two separate takedowns in 2019. According to its statement, Facebook has now banned both companies from using its platforms.

Beyond NewWaves and Flexell, the motivation for maintaining this network remains unclear, as the content varied between the humorous, the benign, and the political. Given the companies appear to be paid-for marketing firms, without insight into their client base, it is unlikely that the true source of this activity will become known. It is this opaque nature of the business that is of particular concern: without clear insight as to who is paying a private company to undertake such activities, the ulterior motive for the information pollution they inject online will similarly remain a mystery, making it nearly impossible to hold those ultimately responsible accountable.

Jean le Roux is a Research Associate, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Max Rizzuto is a Research Assistant with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

The Digital Forensic Research Lab team in southern Africa works in partnership with Code for Africa.