Subscribe

Data delivered to your inbox. Keep up with the latest developments.A marketing company created groups that fuelled fearmongering and conspiracies.

A Facebook page linked to Cape Town-based digital marketing firm Fansgate created at least 33 Facebook groups between January and March 2020 that leveraged fears around the novel coronavirus to build their respective audiences, a DFRLab investigation has found. Fansgate’s director subsequently used a separate but related entity called AppleBerry to exploit these fears and market non-medical face masks to the members of these groups.

Fangate’s for-profit venture had an unintended consequence: in commercializing coronavirus-related fears of group members to market its product, it also created a platform for the propagation of misinformation. The Facebook groups quickly became vectors for the spread of coronavirus mis- and disinformation after the administrator seemingly abandoned them to volunteer moderators.

Parallel the spread of the coronavirus itself, related disinformation and factually misleading information has propagated in a similar manner, quickly jumping around the globe. The World Health Organization referred to the spread of this information epidemic as an infodemic — a public health crisis that has the potential to cause serious harm.

In response to the DFRLab’s investigation, Facebook took action against the companies hosting the groups. “We removed these Pages and Groups for misleading people about their purpose and attempting to evade our prohibition on the sale of medical equipment,” a Facebook company spokesperson said in a statement. “We are grateful to the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab for bringing this information to our attention.”

The DFRLab has reached out to the marketing companies’ owner for comment.

Geographic Transmission

The Facebook groups, which included Coronavirus Philippines, Coronavirus South Africa and Coronavirus (COVID-19) Updates, segmented themselves geographically, and targeted individuals located in Africa, Europe, the United Kingdom, the Philippines and United States amongst others.

Considering that Fangate and AppleBerry are located in Cape Town, South Africa, their interest in the spread of the coronavirus in foreign jurisdictions seems odd. But it is clear that AppleBerryMasks’ motivation is commercial: a marketing blurb uploaded to the page on February 12, 2020, stated that AppleBerry was created to satisfy a need for more “fashionable and upbeat” face masks. This in of itself was strange, as the South African population do not generally wear face masks in public.

It also registered its AppleBerry.shop website on February 15, 2020, which sells face masks for between $15 and $25. The various Facebook groups created by Fangate and AppleBerry are listed under a separate page as AppleBerry “communities.” On March 11, AppleBerry posted veiled advertisements for its “non-medical” face mask on two of the South African coronavirus groups. While similar advertisements were not posted on the international groups, this is likely because AppleBerry has not yet secured an international distributor, according to their website.

Despite claiming that the groups were not created for fearmongering or advertising purposes, the AppleBerry page did both of these things in short succession in March 2020.

On March 10, AppleBerryMasks posted on the Coronavirus South Africa group, drawing hypothetical parallels between South Africa (which only had seven confirmed cases at that stage) and the 631 deaths in Italy at the time.

The sendoff, “What are you doing today to protect yourself and your family?” dovetails with a post it published on the group the following day, in which AppleBerry promoted an “introductory offer” on its non-medical face mask to members of this group.

For only R179–00 (USD $10), concerned members of these coronavirus awareness groups could be the proud owner of a non-surgical face mask that AppleBerry claims “may” protect against the spread of germs in crowded environments.

The AppleBerry website uses heavily disclaimed statements and hedge language that makes it clear that their face masks are not intended for any real medical intervention. Despite this, the store’s news page contains links to articles exclusively about the coronavirus, increasing the suspicion they are using coronavirus fears to market unsuitable face masks.

Cotton face masks, like the ones made by AppleBerry, are not capable of filtering out airborne viruses like the novel coronavirus, and instead act as a barrier. A 2014 study even cautioned healthcare workers, who are most likely to come into contact with viruses, against using cotton masks due to the masks’ poor filtration capacity and moisture retention. The National Institute for Communicable Diseases, one of South Africa’s national public health institutes, has also warned that citizens who are not used to wearing face masks are likely to start touching their faces more regularly, which in turn could theoretically increase the likelihood of contracting the virus.

Carrier networks

DFRLab’s investigation identified two linked networks of Facebook groups. The first network was administered by the Fangate Facebook page, which had amassed more than 91,000 followers since it was created on July 22, 2013. The second network was mainly administered by AppleBerry. In stark contrast to FanGate, AppleBerry’s Facebook page gained less than 300 page follows since its creation on February 9, 2020.

The larger of the two networks was administered by Fangate, and numbered around 100 private Facebook groups, such as unofficial pages for South African brands and football teams, as well as a large contingent of jobseeker groups. The overall impression was that Fangate was operating these groups as a means to gain access to their members for marketing purposes.

Nestled between these Fangate groups was a subset of 33 groups related to the coronavirus. Most of them were geographically segmented, with groups dedicated to the Philippines, Australia, Brazil, the US, and even individual counties within the United Kingdom. By contrast, the AppleBerry groups were thematically limited to the coronavirus. The AppleBerryMasks page created a contingent of 25 groups focused specifically on South Africa, which resembled the groups in the FanGateZA network in many respects.

On March 11, 2020, the DFRLab compared the creation dates and designated administrator of these groups chronologically:

This analysis revealed that AppleBerry was the designated administrator for two groups that were created before its own existence: Coronavirus South Africa and Coronavirus Botswana. This means Fangate, the original creator of both groups, ceded page administration over to AppleBerry after AppleBerry was created. Since then, several of the larger groups (including CoronaVirus U.S.A. and CoronaVirus Brazil) have also been transferred over to AppleBerry from Fangate. This is important, as the transfer of the administrator function established a link between the Fangate and AppleBerry.

This analysis also revealed similarities in the naming conventions used by the pages. Pages created between February 9 and February 21, 2020, were administered by AppleBerry (the exception being Coronavirus Quezon City, which was created and administered by Fangate). These groups were different from the first batch of groups, created by Fangate between January 24 and February 2, in that they were focused on individual towns and provinces within South Africa, as opposed to broader countries or regions.

This more granular geographical pattern was carried over once Fangate resumed creating groups on February 21, at which point it created coronavirus-related groups focused on specific counties within the United Kingdom.

Symptomatically similar

The DFRLab’s investigation noted both networks featured similar artistic renditions of microbes as their cover pictures. A reverse image search of these pictures identified them as renders of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), available on Pinterest, and a stock image of the coronavirus available on Unsplash.

The FanGateZA and AppleBerryMasks groups shared mutual administrators, as seen on the membership pages for these groups. Similar wording was used in the about, description and page rules sections of the groups across both networks.

Many of the groups across both the Fangate and AppleBerry networks used an automated “greeting” system to welcome new members to their respective groups. These greeting posts would either be posted by the Fangate or AppleBerry pages directly, or by the administrators for the groups.

Although the bulk of the groups had either the Fangate or AppleBerry pages listed as administrators, two user profiles belonging to accounts named Trisha Karina and Chris da Silva featured frequently among the lists of administrators for the groups in both networks.

While the similarities in the presentation of both groups already pointed to a nebulous link between the Fangate and AppleBerry networks, a further investigation into these two profiles made the link evident.

Contra-indications

The first of these user profiles claimed to be a woman from Cape Town named “Trisha Karina.” A fan page for Trisha Karina, created in 2013, claims she originally hails from Stellenbosch, some 30 miles east of Cape Town, despite her profile indicating she is from Durban, another 1000 miles further away.

The profile does not contain much by way of personal details, yet it shared many links to Fangate’s coronavirus groups, as well as events promoted on Fangate’s now-closed website. Trisha Karina is a staunch supporter of Fangate projects, and in September 2019 the profile posted favorable reviews to an employment-related page linked to Fangate.

Overall, the Trisha Karina profile appears inauthentic. The profile picture for the account is widely available online, as confirmed by a reverse image search using Google. There is not clear persona evident from the profile, and content it posts inevitably relates back to Fangate. Even an Instagram account associated with the profile only contained stock images of fitness models, and posts on the fan page contained similar content.

The Trisha Karina profile is also an administrator of several Facebook groups created by Fangate and one page associated with AppleBerry. Where the Trisha Karina profile is not an admin, the account has been added to the group as a regular member.

Attempts by the DFRLab to make contact with the Trisha Karina account went unanswered. The account has since been deleted or deactivated, shortly after reaching out for comment.

Typhoid Mary

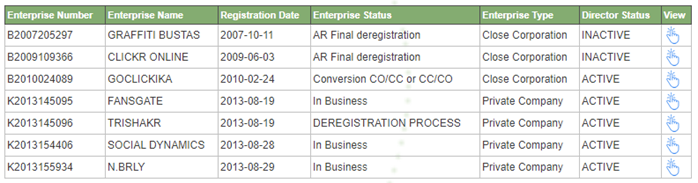

The second profile used to administer these groups belonged to Chris da Silva. The profile itself was devoid of any telling information on the owner’s identity. One of the profile pictures seen on the account history could be traced to a community safety application called Neighbourly. The Terms of Service page on the Neighbourly webpage provided the legal company name, N.brly (Pty) Ltd. Company records revealed that Neighbourly’s sole director is an individual by the name of Chris da Silva.

The same Chris da Silva is also the director of several other companies. Fansgate (registered to the same business address as displayed on the Fangate page) was created in 2013, the same year the Fangate Facebook page was created.

Another of da Silva’s companies called TrishaKR (bearing a remarkable resemblance to the name used for the Trisha Karina profile) was also registered on the same date as Fansgate.

AppleBerry does not appear in the list of companies registered by da Silva, but two phone numbers found on the AppleBerry and Fangate Facebook pages were linked to him using Truecaller. The first number was found in a series of marketing proposal documents on the Fangate Facebook page. The second number was found on the About section of AppleBerry’s page. Truecaller indicated both phone numbers were registered to the same individual: Chris da Silva.

In addition, a WHOIS search of the appleberry.shop domain revealed that da Silva was the individual that registered the AppleBerry website on February 15th.

While in isolation, each of these datapoints could be disregarded as mere coincidence, the confluence makes a compelling argument that Fangate’s director is behind both pages, as well as the Chris da Silva user profile.

All things in moderation

In terms of activity, the groups created by Fangate and AppleBerry positioned themselves as public interest groups: their respective about and information pages give the impression that they were intended to share updates on the spread of the virus, and keep communities safe through the sharing of this information.

Instead, the groups quickly became breeding grounds that proliferated conspiracy theories, misinformation and even disinformation surrounding the coronavirus. Group moderators, appointed by Fangate to keep the community in check, were themselves guilty of sharing links to websites that published dubious or debunked information.

In other instance, the very moderators meant to ensure a group did not spread false or misleading information were doing so themselves. Administrators on the CoronaVirus U.S.A. and the “main” CoronaVirus (COVID-19) Updates groups were seen posting links to Breitbart, ZeroHedge and Infowars.

Fangate’s modus operandi appears to be to create these groups, recruit several local volunteers as moderators and then leave the responsibility for managing group conversations with them.

This can be seen from posts made by the administrators requesting individuals to volunteer as moderators.

After the moderators have been appointed though, the administrators seem to leave the building: posts from moderators expressed frustration at Fangate’s apparent inaccessibility.

This seems similar to what happened with an unrelated jobs group, also administered by Fangate. A user review posted to the Fangate page claimed the group was overrun with adult content and that no moderation was performed on the group at all.

Conclusion

Although the AppleBerry page claimed the local South African and international groups were created to connect communities rather than fearmongering or advertising, AppleBerry appears to have used the groups for those purposes. By marketing non-medical masks in the “occupational safety and health services” category on Facebook, drawing parallels between South Africa and Italy, and asking people to question how they will protect their family, the newly-created company seemed to capitalize on the public’s fear of COVID-19 to make a quick buck. As a result, AppleBerry added fuel to the infodemic fire that makes the work of health care workers on those on the front line of tackling the spread of the virus all the more difficult.

Jean le Roux is a Research Associate, Sub-Saharan Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Tessa Knight is a Research Assistant, Sub-Saharan Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.

The Digital Forensic Research Lab team in southern Africa works in partnership with Code for Africa.